Also

known as Bessel’s Star, Piazzi’s Flying Star, GJ 820 A/B, Struve 2758A/B,

ADS

14636 A/B, V 1803 Cyg A/B, GCTP 5077.00A/B

Finally. A nearby star that just

maybe/possibly/might be visible by naked eye alone.

Well, with a combined apparent magnitude

of 4.8, perhaps barely so, or at least from Howard County. It should be an easy

catch from any dark sky site, other than for its location within the relatively

crowded star fields of the summer Milky Way. And in addition to being of interest

due to its proximity to the Sun, 61 Cygni is also a significant star both

historically and in its own right.

First of all, 61 Cygni is actually two

stars (A and B), gravitationally bound in orbits quite similar to those of

Struve 2398’s two components. It takes 653 years for them to circle about a

common center of gravity at an average distance of 85 AU (approximately the

diameter of Pluto’s Orbit). At their closest, they can be separated by as

little as 51 AU, whilst at the other extreme they move as far apart as 119 AU.

The two stars are both main sequence orange dwarfs of spectral class K,

somewhat smaller than the Sun (0.70 and 0.63 solar masses, respectively), and

correspondingly smaller and cooler. They rank among the coolest, dimmest main

sequence stars capable of being seen without optical aid. Both stars appear to

be the same age, and are older than the Sun (perhaps as much as ten billion

years old, but more probably closer to six). Apparently not members of the

Milky Way’s thin disk population (see the posting for Lalande 21185), they are “just

passing through” from their probable origin in the galactic halo. Evidence for

this is both their low metallicity (about one quarter of the Sun’s), and their

velocity with respect to the solar system – a whopping 67 miles per second,

moving roughly in the direction of Orion’s Belt. Remarkably similar to each

other, it is safe to assume that A and B were formed as a binary pair.

Both

have quite similar rotation periods (35 and 37) days, with their sunspot cycles

being 7 and 11 years respectively. 61 Cygnus A is classed as a BY Draconis

variable, meaning that its sunspot cycle is so extreme (compared to the Sun’s)

that it can fluctuate by as much as 0.5 magnitude as it rotates, turning its

massive starspots toward and away from out view. Meanwhile, the smaller B

component shares a characteristic with the even dimmer red dwarfs of being a

flare star, exhibiting at intervals a sudden and massive brightening across the

spectrum. Such activity makes both stars poor candidates for a place to find

stable enough conditions for life to exist on any hypothetical planet (for

which there is no evidence).

But 61 Cygni is also quite significant for

the role it has played in astronomical history. It first came to prominence in

the year 1804 due to painstaking observations by Italian Catholic priest,

Giuseppe Piazzi (perhaps better known for his discovery three years previously

of the asteroid Ceres). Piazzi noted that the star had detectible motion

relative to the stars around it, and christened it the “Flying Star”. Such

movement is known as “proper motion”. It took another eight years for the

German mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel to bring Piazzi’s discovery to

the attention of the worldwide astronomical community. It was Bessel who

realized that 61 Cygni’s rapid movement across the sky indicated that it was

likely among the closest stars to the sun. This gave him the idea of using the

star to determine the distance to the stars in general.

For until the 19th Century, no one had any

real idea just how far away the stars were. This had been a question bedeviling

astronomers since ancient times. The great Ptolemy, foiled in every attempt to

determine the figure, finally came to the reasonable conclusion that for all

practical purposes they should be considered as infinitely distant. In more

modern times, it was generally accepted since Copernicus that measurements

ought (at least in theory) to be able to be made using parallax. Parallax is

the method by which the human brain is able to perceive what our eyes see in

three dimensions. Hold up your thumb at arm’s length and look at it, first

using only your left eye, then your right. You will notice an apparent jumping

back and forth of your thumb relative to objects in the background. Of course

the thumb isn’t really moving, but the angle of observation is changing as you

move from one eye to the other. Bessel proposed doing the same thing with a

nearby star, using opposite sides of the Earth’s orbit as the “eyes” (see illustration below).

Bessel kept up exacting measurements of 61

Cygni’s differing aspects at different times of the year from 1812 to 1838, by

which time he was able to determine that it appeared to wobble back and forth

with respect to the more distant stars by 0.3136 arcseconds, suggesting a

distance of 10.4 light years. He was off by one light year (61 Cygni being 11.4

ly distant). But despite the 8.8% error, 61 Cygni became the first star ever to

have its distance from the Earth known to any degree of accuracy whatsoever.

In 1911, American astronomer Benjamin Boss

expanded upon 61 Cygni’s astronomical importance by discovering that the star

was one of at least 26 that shared nearly identical velocities with respect to

the Sun, and proposed that this “co-moving group” was physically related

(perhaps the remnants of a former open star cluster). The various members of

this group of fellow travelers are scattered all across our skies, in

constellations as various as Taurus, Virgo, Cygnus, Mensa, and Columba.

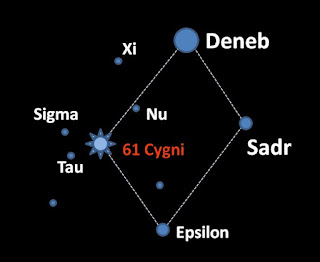

To observe 61 Cygni, you need nothing more

than a clear sky and a pair of binoculars. Start by locating the constellation

Cygnus. If that’s too difficult, then look for the huge “Summer Triangle” of

Deneb, Vega, and Altair. If you can’t locate that, then it’s time to consult a good star atlas. In any case,

once you’re looking in the direction of Cygnus, mark the northwest corner of

the Northern Cross asterism (formed by Deneb, Albireo, Delta and Epsilon Cygni,

with Sadr at the center). 61 Cygni would serve as the fourth corner of an

imaginary quadrilateral at the upper left of the cross (although

it would be by far the dimmest of the four corner stars). If your sky is

moonless and sufficiently dark, you may even be able to spot it with your eye

alone. If suburban light pollution is an issue, a good pair of binoculars

should do the trick. In fact, due to their 30+ arcseconds separation, a pair of

7X50 binos ought to be enough to split the double star into its A and B

components.

But by all means don’t stop there. Pull

out your telescope, and get a good look at this fascinating star system, and

recall to mind how much astronomical history is displayed before your eyes in

this object. Besides, after this “rest stop”, it’s on to one of the most

difficult stars of all on our journey through the Solar Neighborhood – EZ

Aquarii.

No comments:

Post a Comment