Also known as GX/GQ

Andromedae, HD 1326, GCTP 49, BD +43º44, LHS3/4, GJ15A/B, GI 171-047/171-048, SAO 36248, LTT 10108/10109,

LFT 31/32,

Vyssotsky 085 A/B, HIP 1475

The 19th Century was in many

ways a unique period in the history of science, perhaps never to be repeated.

Other than in the field of biology (which was then reeling from the Darwinian

revolution), it was generally felt that “there was nothing left to discover” of

any significance. The almost universal feeling was that all that remained for

future generations of researchers was to extend by one or two more decimal

places the already comfortably established basic facts of nature (the

mind-shattering revelations of relativity and quantum physics being at the time

totally unsuspected). As a consequence, the 19th and early 20th Centuries were

a Golden Age for catalogicians. It was then that much painstaking work was done

on creating massive lists of stars, galaxies, nebulae, craters of the Moon,

etc., that are responsible for so much of today’s heavenly nomenclature.

Typical for the age, when Beer and Madler published their definitive maps of

the Moon’s visible hemisphere in the 1830s, they were so detailed and

comprehensive that they paradoxically practically killed off subsequent serious

study of our satellite for more than a generation.

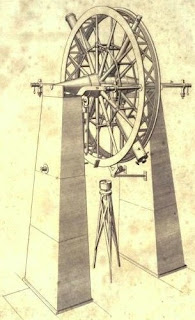

So when in 1806 Stephen Groombridge began

work on his Catalog of Circumpolar Stars

(published posthumously in 1838), he was representative of the spirit of his

times. He spent more than 10 years observing stars down to the 9th magnitude,

using the Groombridge Transit Circle which he himself had designed and built,

followed by another 10 checking and re-checking his work. Groombridge 34 is of

course the 34th entry in his catalog. A glance at the catalog entry shows that

he measured its magnitude at 8.9 (its true magnitude is 8.08), that he had

observed it four times, and made no reference to any companion stars.

His most famous entry is perhaps

Groombridge 1830 in Ursa Major, which for the remainder of the century was the

star with the highest known proper motion (and to this day holds 3rd place).

Groombridge 34 itself is a multiple star

system, similar to Struve 2398. Its two components, A and B, are magnitude 8.08

and 11.06 respectively. Widely separated by at least 147 AU, they take more

than 2,600 years to complete a single orbit of each other.

Observing

Groombridge 34

Now how often will you ever see star

hopping directions that begin with “Start from M31”? But that is exactly what

we are going to do. The Great Nebula in Andromeda, M31, the Andromeda Galaxy,

the Granddaddy of all Faint Fuzzies, is indeed the most convenient starting

point for searching out Groombridge 34. So enjoy the sight for a minute or two,

then slide a bit to the northeast until you come across two nicely-matched 5th

magnitude stars, HD3346 and HD2421 (HD3346 is a bit redder than its neighbor to

the east, but the color difference is not that dramatic.) Using binoculars, you

will see that these two are situated on the left side of a rather pathetically

squashed “W” (see star chart right above this paragraph). All of the stars

making up this asterism are brighter than magnitude 7, so you should be able to

take in the whole thing without any problem.

From this point a telescope is required.

The magnitude 6.11 star just south of Groombridge 34 is 26 Andromedae. (The

magnitude 6.15 star to its right missed out on a Flamsteed Number, and has to

settle for being HD1185.) Let’s zoom into this area, using your widest field

eyepiece. At magnitude 8.08, you should already be seeing Groombridge 34, but

let’s make sure you’re identifying it correctly.

This star chart shows a wide field view of

the final search area. Note how Groombridge 34 is near the center of a box

formed by four relatively bright nearby stars, with 26 Andromedae along the

south side. Once again, by this time our target ought to be in plain sight, but

there is one last rather important error to be avoided. Groombridge 34 is a

double star, and when you observe it you might be tempted to mistake the

extremely close 9.73 magnitude star TYC 2794-1397-1 for the B component of our

objective (as I myself did, the first time I observed this star). The true B

star is a much fainter magnitude 11.06, and is a difficult split to make

without switching over to a much higher magnification (and narrower field)

eyepiece. It can be done, but don’t make the rookie mistake I did!

No comments:

Post a Comment