“For

to him who has will more be given, and he will have abundance;

but

from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.”

(Matthew

13:12)

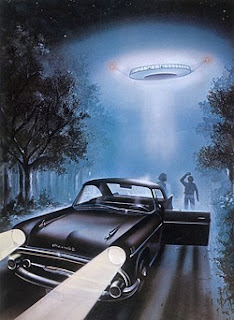

I am old enough to remember the fading

years of the Flying Saucer craze, which began shortly after World War II (and for

some people continues to this day). Its heyday was in the mid-1950s, when it

was possible for totally respectable people to openly say without the least

embarrassment that they believed the Earth was being regularly visited by

extraterrestrials. “Saucers” it seems were being spotted everywhere… well,

almost everywhere. There was a curious inverse correlation between population

density and number of sightings. The more rural a location (the deserts of the

American West and similar wildernesses were best of all), the more likely one

was to see one of these things. Somehow or another, our interplanetary

interlopers never got around to flying over New York, Moscow, or London. They

preferred Siberia, Tibet, the wilds of New Mexico, or the (then) dark lanes of

rural Ohio.

It wasn’t until many years later that I

started wondering about why this was so. Not personally believing in visitors

from distant worlds, I figured the answer lay somewhere within human thought

processes. What was it about the Far West, the back forty, or a deserted

country road that lent itself to such encounters?

Well, first of all we have to keep in mind

that the world was one heck of a lot darker at night back then. Light pollution

was not a problem, once one got out of the cities. So there was far more to

see. The Milky Way was a band of fire across the sky and you could read by the

light of Venus or Jupiter. Instead of today’s pathetic sprinkling of a few dots

of light, bravely battering their way through the combined spillage of millions

of poorly shielded streetlights, the night sky was positively ablaze with

wonder and color. So there were far more chances of mistaking Sirius or Mars at

opposition for a mysterious spacecraft.

But more importantly, there is something

about driving far away from other people, going deep into the wilderness, that

seems to cause one to somehow think he is in fact physically closer to the

stars. After all, Space was the New Frontier, and how better to get close to it

than by actually going to the frontier, right here on the Earth? It’s a curious

mindset, and a bit amusing if you stop and think about it, but nevertheless

still quite understandable.

Nowadays, with the relentless advance of

light pollution over the countryside, we have entire states where it is

impossible to see the Heavens in all their unspoiled grandeur. Living as I do

in Maryland, I am forced to travel hundreds of miles to get away from the

leaden gray skies that one sees in the Baltimore-Washington corridor. I

consider myself lucky if even just two or three nights a year I get the chance

to see the stars as they ought to be seen.

So there really is something to the idea

that heading into the wilderness brings one closer to the Milky Way. Some years

ago, I made a solo trip by car all the way across the country (and back again),

starting in Maryland and going as far as Monterey, California. By the time I

had made it to Salina, Kansas, I was in Dark Sky country. That night, I drove

out to Mushroom Rock State Park, about 15 miles outside of town. I was

completely alone, not having seen another human being for the last 6 or 7 miles

of the drive (the final 4 of which were along a dirt road). It was still light

when I set up in the absolute stillness of complete solitude, and waited

somewhat impatiently for it to get dark. Night, when it finally arrived, seemed to come like the turning off

of a light switch. I looked to the southwest (it was mid-October) and what I

beheld took my breath away. The Milky Way in all its glory (I was looking

straight toward the center of our galaxy) was a blaze of light that went right

down to the horizon and arched overhead to be lost somewhere to the north. It was

so bright that it actually cast a shadow. And it wasn’t just bright – it was colored!

Electric blue star clouds interspersed with gleaming yellow spiral arms. Ruby

red, gold, and brilliant blues sparkled along its entire length. I was shocked –

that’s the only word for it. I was so used to looking up at the pale, barely

visible Milky Way that I had seen under suburban Maryland skies a hundred times

or more, and had no idea… simply no idea.

I looked at M24, the Small Sagittarius

Star Cloud, through my 15X70 binoculars (pictured below, with parallelogram mount), and literally wept at the sight. Using

binoculars gave the view a 3-dimendional quality, while preserving the wide

field aspect of the view. It was blindingly obvious that I was looking past

multiple stellar aggregations to catch a glimpse of the outer regions of our

galactic center. I have no idea what else I observed that night, because I kept

coming back to M24 again and again and again. I simply could not get enough of

it.

There were several other opportunities on

that trip (mostly in New Mexico) to experience dark skies, but that first

encounter is what most stays in my memory. And as much as I enjoy reliving the

experience, it saddens me in a way too. I think about the hundreds of millions

of people who have never seen what our universe truly looks like. I feel that

much of our contemporary spiritual poverty stems from our estrangement from the

natural world about us. There should be no mystery to the loss of faith and rise in moral

relativism in an environment where one seldom if ever encounters an horizon

further off than a city block, where concrete takes the place of soil, and

electric lighting that of the stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment